The M-130 Flying Boat was a significant technological achievement in the world of commercial aviation. It was such an achievement that elements within the Japanese Empire were concerned with what was perceived as its ability to allow the United States to expand into the South Pacific and Asia. Long before the airline had the official go-ahead to provide passenger and air mail service across the vast ocean (a feat thought to be almost unobtainable or profitable), Pan Am was making a strong reputation as a safe and reliable air carrier.

The M-130 Flying Boat was a significant technological achievement in the world of commercial aviation. It was such an achievement that elements within the Japanese Empire were concerned with what was perceived as its ability to allow the United States to expand into the South Pacific and Asia. Long before the airline had the official go-ahead to provide passenger and air mail service across the vast ocean (a feat thought to be almost unobtainable or profitable), Pan Am was making a strong reputation as a safe and reliable air carrier.

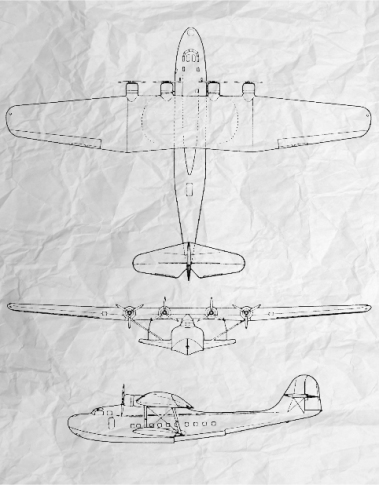

Designed at a cost of $417,000 (today around $9,040,649) by the Glenn L. Martin Company to meet Pan Am Airway’s need for a trans-Pacific aircraft, the M-130 was to be the safest and most luxurious passenger aircraft in the world at that time. There are no indications that the three aircraft built (Philippine Clipper, Hawaii Clipper, and China Clipper) ever had a mechanical or structural failure and each of the three losses had been blamed on pilot / navigational error. A revised fourth aircraft was later built for the Soviet Union and designated the M-156 for the longer-range capabilities needed for the massive country. It is interesting to note that the numbers 130 and 156 in the aircraft designations were selected because those were the wingspans of the M-130 and the M-156 respectively.

The M-130 boasted an all-metal framework, seamlessly marrying aerodynamics with the most potent engines of its era: the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp was a powerful 14-cylinder radial aircraft engine churning out a formidable 830 horsepower. It utilized the most advanced method of cooling anywhere in the world by designing a unique flow of baffled air over the radial cooling fins. It’s worth noting that the Hawaii Clipper received these upgraded engines (boosted to 950hp) shortly before its loss which actually caused great concern for the military. The engines, considered “military grade,” were a coveted asset and never left unguarded. As a measure of caution, each aircraft was towed from the water each night and housed within a hanger for maintenance as well as protection from possible saboteurs or economic spies. The engines were eventually used in famous US fighter and bomber aircraft such as the P-47 Thunderbolt, Grumman F6F, and Vought F4U Corsair among others. It would be easy to understand why an opposing military would want to seize such a sophisticated engine if given the chance. Although Japan had been licensed to produce a Single Wasp engine, it was not allowed to produce the Double Wasp.

Manning each M-130 was a crew of 6-9 individuals, including the Captain, First Officer, Junior Flight Officer, Engineering Officer, Assistant Engineering Officer, Radio Operator, Navigation Officer, and cabin attendants. Moreover, the aircraft was equipped with a meticulously thought-out emergency kit, brimming with essential provisions.

Find more information, stories, photos, and video clips here on The Lost Clipper’s Facebook page.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Hello Guy, I was wondering, were there any Japanese engines similar, if not the same as the P & R R-1830 Twin Wasp? Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there Miles,

While I’m no engine expert, I did interview one at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base who is a technology transfer expert and he wrote up an 8 page document on that very question. I would be happy to share it with you if you will give me an email address to send it. Long and short of it though is that there were indeed similarities with American, Herman and British engine technology (thru licensing deals they had and some questionable acquisitions). I have not seen a clear clone of an American engine although some extremely similar partial designs do exist.

LikeLike

Note that the picture on this page that sits above the caption “The M-130 Flying Boat” isn’t an M-130. It is the larger Martin M-156, registration NX19167. the twin tail is the most obvious feature, but there are other subtle differences if you look closely. The M-156 was intended to compete with the Boeing 314 for Pan Am’s next flying boat purchase, but Pan Am chose Boeing over Martin. The sole M-156 was sold to the Soviet Union, and, I believe, operated in the Soviet Far East.

LikeLike

Thanks for this note Axolotl. Yes – this photograph has gotten this observation a couple times so I hope we have finally corrected it. If you desire, we have a nice deep dive into the M-156 on this website.

Best,

Guy

LikeLike

Assuming that the last position report was even reasonably accurate as to the actual location of the Hawaii Clipper, Truk Lagoon was about 1500 miles away in roughly the opposite direction. The Clipper had already been in the air burning fuel and engine oil for eight hours. Is it even within the capability of the aircraft to make that flight?

LikeLike

Hello Hank and thanks for your post. I retraced the clipper route and it falls within the flight range capability for the aircraft with a few hours to spare. Of course I have not taken into account headwinds and other weather deviations (flying below or around turbulent clouds) however the journey is totally feasible. Mileage wise – the route is slightly less than the Treasure Island to Honolulu leg of flight #229.

Cheers!

Guy

LikeLike

OK Guy, I guess that the distance was within the still-air range of the M-130, but the CAA calculated that when they left Guam they had enough fuel for 17 hours and 30 minutes of flight. At the last reported position they had already been the air for 8 hours and had travelled approximately 950 miles from Guam. That left them 9 hours and 30 minutes air time to cover another 1500 miles, and those two figures don’t seem to mesh very well. I’m completely new to this discussion, but I just wondered about this?

LikeLike

The 14 cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-1830 was not used in either the P-47 or the F6F both of these planes were equipped with the 18 cylinder P & W R2800 engine with 2000 HP. The P & W R-1830 was used in the DC-3/C-47 and the Grumman F4F Wildcat. It was and is a good and reliable engine.

LikeLike

It may have already been mentioned, but this is not a picture of a M-130. It is the M-156 “Moscow” Clipper which was sold, along with the production tooling to the USSR.

LikeLike

Thanks Scott. Yes you are correct. The issue is that WordPress likes to shove a random photo in there every now and then so we have to manually change it back again. Thanks for shooting us an E!

Best,

Guy

LikeLike

Continues Sources:

17. http://www.pw.utc.com/About+Us/Classic+Engines/R-1830+Twin+Wasp

18. Janes All the Worlds Aircraft – 1935

19. http://www.dc3history.org/dc3.htm

LikeLike

Hello Miles, according to a US Air Force reverse technology engineer – he has responded that there are some similarities to the Twin Wasp but that there were also other influences. Here is an except of his investigation:

=====================

Based on extensive research, I have concluded that the Sakae series of engines used by the Mitsubishi A6M Zero-Sen fighter is not a derivative of the Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp that powered the Pan Am M-130 Clipper. Rather, it appears the design of the Sakae was largely indigenous with only remote engineering influences by the U.S. Pratt & Whitney Wasp and the British Bristol Jupiter radial engines.

The Sakae (Prosperity) engine series was a product line from the Japanese engine designer/manufacturer Nakajima. It was used by both the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) Air Forces. “Sakae” was the navy designation. The army called the first of the series the Ha-25 (Ha for Hatsudoki (Engine)) and later versions were designated Ha-105, Ha-115. Navy designations for the same engines were Sakae 10, 20 and 30 series. It was the most widely produced Japanese engine during the war and powered fighter, bomber, and transport aircraft. It is most widely recognized as the power plant for the IJN Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter series.

Like the Jupiter, the Wasp was also a world-class radial engine. The Wasp exhibited exceptional performance, capturing many records shortly after its inception in 1925. It also possessed some innovative l mechanical design features. The Japanese government directed their engine producers to develop an indigenous design capability as early as 1930. Nakajima complied with the government directive and began to develop their first engine.

To reduce the technical risk in their first design, Nakajima adopted features from engine models they were familiar with. According to sources, “Nakajima then tried to combine good points found in Jupiter design with the rational design of the US made Wasp.” As a result, Nakajima engineers developed the 9 cylinder, 1470 in3, 450HP Kotobuki (Auspicious) engine in 1930. Several developmental models were constructed and tested before the production configuration of the Kotobuki was established in 1931.

The Kotobuki engine was further improved and developed into the Hikari (Light) engine, which featured a greater displacement (1990 in3) and higher power output (720HP). However, the Hikari had nearly exhausted the potential of the basic engine configuration. The Japanese engineers realized a two-bank design was needed In order to obtain greater power output. In 1933, a 1,000HP class, Ha-5 prototype was completed, which was a 14-cylinder two-bank design that utilized the bore/stroke of Kotobuki.

The motivation to develop beyond the single-bank radial engine came from the aircraft industry. Airplane design was rapidly evolving and producing larger aircraft that demanded larger engines to power them. Single-bank radial engines had reached their maximum potential with nine-cylinders. Increasing the displacement of these engines to obtain more power caused a disproportionate increase in weight. Alternately, increasing the number of cylinders in a single bank rapidly increased the diameter of the engine with an attendant increase in drag and weight. Radial engine designers quickly recognized the solution was to add a second bank of cylinders. The first to do so was the French company Gnome-Rhone. In 1929, Gnome-Rhone produced the 14-cylinder two-bank 14K Mistral Major, basing the design on their earlier single-bank engines the 7K Titan Major and 9K Mistral. The first test examples were running in 1929. Pratt &Whitney followed with their first two-banked engine, the R-1535 Twin Wasp, around 1932.

Conflicting information exists regarding the development of Nakajima’s first two banked engine. The most reliable source author states Nakajima’s first two-bank design was the Ha-5, but he provides no information on its development. Additional information on the Ha-5 is very limited. Source 3 states the Ha-5 used the cylinder design of the Kotobuki and that it was eventually rated to 1,500HP. The Ha-5 apparently powered a few military aircraft in the mid-1930s.

Significantly, Source 3 states, “At the same time, an engine was developed upon the Navy’s request called “Sakae”, of which the Army name was Ha-25.” The author leads the reader to believe the IJN submitted requirements to Nakajima for a new engine at the time the Ha-5 was being developed. However, Source 2 provides a different explanation. It states, “The engine (Sakae) was designed by Nakajima after acquiring a license for the French Gnome-Rhone 14K,” leading the reader to conclude the Sakae is in some way derived from the Gnome-Rhone 14K. Source 3 contains no mention of Nakajima acquiring a production license for the 14K.

I (our Hawaii Clipper Research Engineer) have developed a hypothesis that reconciles the two sources. I believe Nakajima’s first two-banked engine was the Ha-5. Its development provided Nakajima the knowledge to develop the Sakae. Timeline analysis supports this contention. The Ha-5 was installed in aircraft that appeared in the middle 1930s. The Sakae began to be installed in aircraft no earlier than the 1939 timeframe, suggesting development of the Ha-5 preceded work on the Sakae. I assess the role the French engine served was as a catalyst for Nakajima and not as a design template as suggested by the author of Source 2. This hypothesis addresses the relationship between the Gnome-Rhone 14K and Nakajima and does not conflict with Source 1.

I propose the French engine’s success may have reduced Nakajima’s perception of the technical risk associated with constructing a two-bank design. It is important to recognize that in the early 1930s, Nakajima possessed limited design experience. Prior to the Ha-5, the firm had developed only one new engine (Kotobuki) and one performance-improved variant (Hikari) from it and both of these were single-bank radial engines. The engineering required to develop a two-bank engine is more challenging than for a single bank engine, but Gnome-Rhone showed it could be done with the knowledge and technology available at the time. Nakajima may have been further motivated when Pratt & Whitney began work on their Twin Wasp.

Japanese Access to Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp Engines

The Japanese apparently had been granted access to the Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp before the disappearance of the Pan Am Clipper. Source 19 thoroughly describes the Japanese acquisition of the production rights to the DC-3. According to the text exhibited on the website, the Mitsui aircraft manufacturing firm purchased the production rights to the Douglas DC-3 on 24 February 1938, with the first Japanese fabricated DC-3 appearing in September 1939.

The article goes on to describe how they “…replaced the Pratt & Whitney 1,000 hp engines they imported with 1,000 hp Mitsubishi Kinsei 43 radial engines.” The “1000 hp” Pratt & Whitney engines that powered most DC-3 models were Twin Wasps. The article leads the reader to conclude Twin Wasps were purchased from Pratt & Whitney until the decision was made to switch to the Kinsei.19

The Kinsei was a two-banked radial engine in the 1000HP class, developed and produced by Mitusbishi. Detailed technical information on the Kinsei may be found in Source 13.

The Case for Technology Transfer

The narrow window between the time the Hawaii Clipper disappeared (July 1938) and the initial production of the Sakae engine (mid-1939) does not readily support a case for a major transfer of technology.

First, there was no disruptive technology possessed by the U.S. that was critical to the development of the Sakae engine. In fact, there was very little variation in the technology employed by the major protagonists of WW II. In addition, the one year window between the time the Clipper disappeared and the production of the Sakae was too narrow for Nakajima to reverse engineer the Twin Wasp and incorporate selected technologies in time for serial production.

Summary

I believe the body of evidence uncovered in this investigation is very convincing that the Sakae engine is neither a copy nor an immediate variant of the Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp. Therefore, if the Japanese abducted the Hawaii Clipper, it was not to obtain its engines [ but to intercept the 3 Million Dollars intended for Chinese aid / resistance against the Japanese invasion of China]. For decades, Japan had clearly demonstrated the ability to manufacture modern power plants, and since 1930, the ability to indigenously develop competitive designs. Several of the sources clearly show much of the aviation technology Japan desired was available on the open market and that they overtly took advantage of it. In light of the alternatives available to Japan to acquire modern aviation technology, it is difficult to believe Japan would engage in a high-risk acquisition action.

=================

Source List:

1. Green, William, War Planes of the Second World War – Fighters-Volume 3, Doubleday & Co. Inc., 1961

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nakajima_Sakae

3. http://www.ne.jp/asahi/airplane/museum/nakajima/nakajima2-e.html

4. http://www.enginehistory.org/Japanese/nasm_research.htm

5. http://www.pw.utc.com/vgn-ext-

templating/v/index.jsp?vgnextoid=432a26c6d9903210VgnVCM1000004f62529fRCRD

6. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bristol_Jupiter

7. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnome-Rh%C3%B4ne_14K

8. http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/H/a/Ha-5_aircraft_engine.htm

9. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitsubishi_Kinsei

10. http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/K/i/Ki-21_Sally.htm

11. http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/K/i/Ki-30_Ann.htm

12. http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/K/i/Ki-57_Topsy.htm

13. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitsubishi_Kinsei

14. http://www.enginehistory.org/Japanese/KINSEI.pdf

15. http://www.douglasdc3.com/japl2d/japl2d.htm

16. http://en.wikipedia.or/wiki/List_of_aircraft_engines_in_use_by_Japan_during_World_War_I

LikeLiked by 1 person

Guy, did the Japanese ever have similar Twin Wasp engines in any of their aircraft? And are the engines in the Kawanishi H8K or similar bombers related to the R-1830?

LikeLike

The F6F, F4U AND the P-47 ALL used the Pratt & Whitney R2800 engine (2800 cubic inches) and NOT the earlier R1830 (1830 cubic inches). The R2800 was a full generation or

more advanced (18 cylinders) and put out MORE than double the power of the 1830 (Up to 2500 horsepower). It had little if any direct relation to the 1830 (14 cylinders) except it was a P.W. radial type engine. The 1830 was used in Douglas DC-3, B-24 Liberator, Grumman F4F Wilcat and Curtiss P-36 aircraft starting in 1932. The 2800 was a big high performance secret as war loomed…but the 1830 was a lower power transport engine by that time. The zero fighter had engines with output power of as much, if not more than the 1830 ever had….I’m fairly certain the Japanese would have had examples of the 1830

(since it started being built in 1932) for many years before the war. The zero’s (14 cylinder) Nakajima Sakae engine was likely (if not certainly) a unauthorized “copy” of the P.W. 1830 and was already in mass production in Japan.

So really, would be fairly HARD to understand why an opposing military would want to seize such an engine.

LikeLike

Hi Jim and thanks for your excellent observations. The Martin 130 was indeed very modern for its time and set standards for being sleek, powerful and elegant. The four P&W R-1830-S2A5G Twin Wasp radial engines with 620 kW (830 HP) that were originally onboard were allegedly swapped out for more powerful variants of the Twin Wasp. Some previous Pan am pilots I have interviewed had suggested that Pan am was actually conducting some testing with experimental engines and I am looking into Engineering Log books to collaborate on this theory. One of the mentioning was work on a R-2800 engine however this has not been proven yet. I personally suspect the actual hijacking was not for the engines because of some of the reasons you state but more about intercepting three million in gold bank notes and keeping them out of the hands of the Chinese nationalists.

In the meantime, the aircraft was last certified as air-worthy on July 23, 1938 with a Certificate of Airworthiness (License) Number NC-14714 on that date with an interesting note in a navigators log book removed from the Hawaii Clipper two weeks prior which mentioned “the new engines” so I am hopeful we can get a better idea of which variant they were.

Thanks again for checking in and helping to keep the Lost Clipper error free (as much as possible).

LikeLike

Hello Diana, Your grandfather was my fathers first cousin. My grandfather, Victor, was uncle to Jose Maria Sauceda.

LikeLike

Victor, I sure would appreciate it if you would get on our family Facebook page. I would very much like to chat with you about family ties over on FB so as not to fill up Guy’s site with our family history. Hope to see you at our Somerset Sauceda Family Facebook page.

LikeLike

BRAVO GUY! You will find your answers, I am sure of it.

LikeLike

Hello Guy,

I want to direct you research to “Flying the Oceans – A Pilot’s Story of Pan Am” by Horace Brock, Published by J Aronson Inc copy write 1978. Brock was a Pan Am Captain that started in flying boats and retired flying Boeing 747s. He was with the relief crew in Manila and was scheduled to fly on the Hawaii Clipper back to Alameda July, 1938, as 1st Officer. Brock was of the opinion that a tropical storm brought the clipper down.

Brock had flown with Captain Leo Terletsky during a tropical storm and refused to fly with him again. Pan Am’s Chief Engineer, Andree Priester, wanted to pull Terletsky’s credentials. Most flight crew refuse to fly with him. However, Terletsky was a close personal friend of Igor Sikorsky (they were both White Russian Expats). Sikorsky pressured Trippe to retain Terletsky. Remember that Sikorsky provided 95% of the planes Pan Am flew in 1938.

Here is another consideration. Captain Ed Musick was Pan Am’s chief pilot and told biographer, William S. Grooch, From crate to clipper with Captain Musick, pioneer pilot, Longmans Green and co; First Edition edition 1939, that the M-130 was unstable on every axis and exhausting to fly. Brock also speaks to that in his book.

As fun as it is to speculate about something nefarious, I firmly believe that Terletsky lost situational awareness in the storm and flew that clipper into the ocean. Big ocean – small clipper. It’s the stuff of fiction and not supported by facts. That said, I will follow your research with great interest and wish you success.

Contact me through my website if I can be of any service,

Cheers! Jamie Dodson, Author of the award winning Flying Boats & Spies. http://www.nickgrantadventures.com

LikeLike

Excellent! I love this exchange of information, it is truly the type of treasure that makes this project alive. You bring out some points I have seen before, especially the reality that Leo was a nervous flyer and frequently depended on his first officer to lend their confidence into his decision making. Mark Walker, the first officer on trip 229, was an extremely competent pilot and knew well Terletsky’s limitations. I personally believe he knew his own strentghst and was sure he could counter balance Leo’s low self confidence. With that being understood, it still does not explain the eye-witness testimonies and multiple accounts of the crew being burried in a concrete slab in Truk Lagoon. IF, and it is a HUGE if, there are 15 Americans in that slab that I stood on last year, and thru DNA confirmation, then, perhaps the crew of the Hawaii Clipper met a fate more gruesome than crashing ar sea. Stay tuned!

LikeLike

Glad that you liked it beacuse I posted it again – dooh! I missed your reply. Oh well, I will post your site to my FACEBOOK Page and my website. Sorry to clutter your webpage.

Have you read Robert Gandt’s “SKYGODS, The Fall of Pan Am”? (http://gandt.com/) By all acounts Walker was a good pilot but Terletsky was a SKYGOD and not likely to listen to a mere First Officer.

Best of luck finding the answers to an amazing mystery, Jamie

LikeLike

I am inclined to give this evidence a lot of weight in resolving the mystery. The pilot’s skills are questions as is the quality of the Martin design. Only four were built?

I don’t find the evidence of a Japanese intervention to be nearly as compelling.

LikeLike

Thanks David. The actual reason that I feel carried the most weight in why more M-130’s were not purchased was not so much about safety or design but pure economics. There were some early troubles with the lower fuel tank but those were quickly resolved. Leo Terletzky, the Captain of the Hawaii Clipper, was a very experienced pilot and joined PAA in 1929 after being a pilot for hire to charted aircraft. There were some rumors within the flying ranks that Terletzky would “freeze up” on the wheel during sever or turbulent weather but he did know how to fly and make split second decisions. The first example that comes to mind is August 13, 1933 when he was flying a Pan Am Clipper and endured a gunfire attack while waiting to leave Cuba with besieged Secretary of State Dr. Orestes Ferrara and his wife aboard. Here is an excerpt from a Trenton (NJ) Sunday Times-Advertiser, August 13, 1933 (Source: Woodling):

Days after an August 1933 revolution ousted Cuban dictator Gerardo Machado, a friend of Trippe’s who once had a Clipper aircraft named after him, Capt. Leo Terletzky, prepared to pilot a Pan Am flight from Havana to Miami. Takeoff was delayed when a most-wanted Machado associate sneaked into the Pan Am dock by reportedly hiding under his wife’s skirt in a taxi and bribing his way onto the Clipper. A Pan Am manager demanded the ex-Cuban official disembark, declaring the American-flag airline “couldn’t be involved in a revolution,” but the Machado crony brandished a revolver and threatened to shoot if anyone dared to drag him away. At that point, Terletzky took the controls and flew the seaplane out of Havana as a mob of anti-Machado vigilantes opened fire, and bullets just missed the captain and the fuel tanks. The plane arrived safely in Miami, where the Cuban expatriate rewarded Terletzky by giving him his gold watch.

Not too shabby I would say. On the M-130 issue; Martin was building these boats at a loss with the hopes of making a whole lot more of them later however the three that went into service for PAA and the M-156 (SP 30) Russian Clipper where all that were completed and the Boeing 314 took the lead in production. As a side note, the Russian Clipper flew for Areoflot until 1944 when it was scrapped. Each fully equipped Martin cost $417,000 at a time when the largest contemporary land-plane, the Douglas DC-2, cost $78,000 apiece.

LikeLike

A friend of mine gave me a photo of the Hawaiian Clipper back in the 90’s. It is an 8×10 in good condition. It is being serviced at the time, but I have no way of knowing where. Could it be Oakland or Alameda or ??. I can send an image via Email if anyone is interested. Thanks in advance. Lee

LikeLike

Thanks Lee, I have seen a few of them but there are always others that have slipped through the cracks of time. If possible, give it a scan and I’ll host it here and give you proper credit.

Best,

Guy

LikeLike

I have always had an interest in the Martin M-130 clippers.

I am 82 years old and grew up in the age of Golden Aviation.

I am interested in contact with those that also have an interest in the Clippers.

LikeLike

Keep your seatbelt on Elmer, the ride is going to get very interesting.

LikeLike

You are the exact age as my dad, I am 57, I just watched charly chan treasure island 1939 and it starts w/ chain as a passneger on the M130 ariving in SF airport. How very diffrent it was on the plane compaired to today. It must have been realy something flying in one of those planes w/ wide open bench seats and how eveyone is dress nice, fancy glass ware and the people walk around at will and smoke, think of the what it’s like now,

LikeLike